Trousers down, trousers up

By the time I show up at Glyndebourne for the start of Season 2019, the remarkable, intricate machinery of the Festival has already been rumbling along for about six weeks, since rehearsals began back in the chilly mornings of March. But it’s only now, in late April, that the costumes are ready to put in an appearance and the dressers have been summoned. Every year, when I step through the stage door on my first day back, it feels as if no time has passed at all, and everything in this backstage world of wonder feels intimately familiar. The cheery smiles from the security staff, the squeak of wheels on a double bass case, laughter echoing in the lift shaft.

By the time I show up at Glyndebourne for the start of Season 2019, the remarkable, intricate machinery of the Festival has already been rumbling along for about six weeks, since rehearsals began back in the chilly mornings of March. But it’s only now, in late April, that the costumes are ready to put in an appearance and the dressers have been summoned. Every year, when I step through the stage door on my first day back, it feels as if no time has passed at all, and everything in this backstage world of wonder feels intimately familiar. The whiff of flowers from the stage door desk. The cheery smiles from the security staff, the squeak of wheels on a double bass case, laughter echoing in the lift shaft.

The Circle Level kitchen stinks of instant coffee, and both the kettles are rattling furiously, belching steam. Shy spring sunlight is shining through the wall of floor-to-ceiling windows in the green room as, bleary-eyed and winter-worn, the dressers greet each other with hugs and high, giggly voices. I receive compliments on my new water flask, so we are off to a good start. Pretty soon, the team of eighteen women has gathered, and we have pulled together a motley collection of squashy armchairs and stools for a day of ‘dresser training’ - a reacquaintance with the various whys and wherefores of the job, and an introduction to the shows that we will be working on.

When people ask my colleague Blossom what the job of theatrical dresser entails, she replies, ‘trousers down, trousers up!’ And, well, yes, that pretty much covers it. We are essentially there to get the performers in and out of their costumes, particularly with the quick-changes, which can often feel a bit like a Formula One pit-stop when stage management are standing by, counting down the seconds as you fly through fiddly buttons and stiff catches in the light of your head-torch. The more pastoral elements of the position are not normally listed in the job description — but if you are able to stay calm, keep a clear head and form a bond of trust with the artists you’re working with, I’d say you’re off to a good start.

This morning, I am epically tired after a finishing a commission to a tight deadline, but Boss Lucy has brought in a pile of jam tarts and French Fancies, and I lurch through the morning of admin on a whizzing sugar rush, crumbs sparkling on my fingers.

We get a rundown on how not to make social media blunders when sharing opera-related content. Contracts and health-and-safety forms are exchanged, security pass-cards are handed out, and lockers are assigned.

When we break for lunch, I take my shiny new lanyard and head over to the Nether Wallop restaurant (a fancy turn of phrase for a kick in the groin?). I fill a little cardboard box from a selection of salads, and take it to a hidden corner in the gardens, where I lie down for a sunlit nap among the daisies and bluebells, feeling like a flower fairy.

The afternoon is all about Berlioz’s The Damnation of Faust, which is being directed by Richard Jones. Crammed into ‘the mothership’ — the top-floor rooms that comprise the headquarters of the Running Wardrobe department (so-called because we look after the costumes during the running of the show), we crowd around a computer monitor and watch a video recording of Jones giving a model-box presentation of his vision for the production. He reaches into a perfectly scaled down model of the set design and moves tiny pieces of scenery around, while his costume designer Nicky Gillibrand flaps costume drawings at the small assembled audience. I am blown away by the story — a soul is sold to the devil in a bid for the romantic dream! Maligned spirits! Drugs made from magical flowers!

We venture down to the costume store in the basement of the building to take a look at the costumes, dangling from black-painted float rails among a forest of moth traps. Beneath the harsh glare of fluorescent strip lights, the astonishing, painstaking work that’s gone into the costumes is plain to see. Not much is ready yet though, apart from some eye-popping codpieces for the dancers, which come complete with rampant pubic hair spilling out around the edges.

Next, we file upstairs and pass through a magical red door with a sign on it that reads, Silence. Stage. On the other side, is another world. I always feel a rush of goosebumps when I step onto the stage. This is where the real magic actually happens, and as we stand about in the wings, I can feel the atmosphere literally humming with it. A rehearsal is happening in the main stage area, so we creep around as quietly as we can, our shoes soft on the black hardwood, murmuring to each other in low voices. The ‘workers’ are up — strip lights that flood everything with bright luminosity, so we can clearly see what we are looking at. I crane my head back and stare up into the labyrinthe of rigging and flies high above our heads, and marvel at all the trussing, cables, ropes, and machinery that I don’t understand. Boss Lucy points out where our quick change booths will be set up in the wings, and this is where many of us will spend most of the duration of the show, camped out in our ‘backstage blacks’ so that we won’t show up amid the shadows and glitter-laced dust.

Finally, we slip through a secret door in the back of the kitchen to sneak into the auditorium, quietly tripping over empty seats and hidden steps in the dark as we peek at the rehearsal in progress. Faust himself, played by tenor Allan Clayton, is on the stage, dressed in a black T shirt, baggy jeans and trainers. He is already managing to imbue his wild eyes and even wilder hair with pathos and poignancy, while a répétiteur’s billiard-ball head bobs at a glossy, black grand piano in the pit. Meanwhile, the dressers are hissing in the shadows about when the next staff bus will leave, and a little while later, we slink out to catch it.

Devilish work

‘So Pearl, you’re going to need to be over here to collect the masks.’ I am led across to the back of the set, and stationed with a basket by a towering structure of steps labelled ‘DAM OF FAUST TREAD UNIT A’. Blue fairy-lights are gaffa-taped to the framework, lighting the way.

The Glyndebourne staff minibus is weaving its way from Lewes to the opera house, and I am sitting next to Blossom. Her giant glasses are perched somewhere towards the end of her nose, and she has a large basket on her lap. ‘It’s my ironing,’ she says, cheerfully practical as ever. ‘I’m going to do it in the lunch break.’ She has even brought her own iron, which makes me smile as the bus pulls over to pick up some singers from outside of Tesco.

After being deposited at the Stage Door, Blossom and I head up to the top floor in the gently-complaining lift. It gets stuck so regularly that I often find myself holding my breath as it grinds through the levels, and no one is supposed to use it to get to the stage during a performance, just in case. Glancing up, I notice that the marker-pen drawing of a cat’s bottom is still loitering in the corner, where it has been for the past few years.

The Running Wardrobe ‘mothership’ is a hive of activity. Boss Lucy is handing out reams of stapled sheets of paper. These are our show plots, with our names pencilled on the front page, and the movements throughout the show of our assigned artists already marked out in orange high-lighter pen. Their entrances and exits on and off the stage are listed, timed to the second, and their costume changes are carefully detailed. These usually happen either in the dressing rooms or in the side-of-stage quick-change booths. ‘Out of black trousers and patent shoes, into blue trousers and lace-up boots. VV quick!!’ On separate sheets we have meticulously comprehensive lists of all costume items, right down to socks, bras, show pants, watches, earrings, and pocket handkerchiefs. It will our job at the beginning of each evening to comb through the items on the dressing room rails and the bit bags, which contain all the odds and sods, and we will have to hunt down anything that might be missing. Usually, missing things will have turned up in someone else’s dressing room, or if they got lost on stage, there’s a chance that Stage Management will have them. Very often, singers accidentally go home in their show socks and forget to return them. Replacements will be procured, but not without a disapproving frown.

Plastic laundry baskets clatter in the corridor as the dressers grab a few each and load them up with freshly laundered towels.

I have been allocated to the Ladies’ Chorus, and I hike my baskets under my arm as I head down to their dressing rooms, stopping off at my locker on the way. I pull out a black apron, festooned with emergency safety pins. My show notes fit into the giant pocket on the front, and I also add in a couple of pens, a small notepad, a head torch, Polo Mints, and an old iPod that I use as a timer.

The Ladies’ Chorus room is full of noise. The (mostly young) women have been rehearsing together for several weeks by now, so they are all familiar with each other and the chatter flows easily. The room is split into ‘bays’, each one consisting of six desks, complete with individual Hollywood-style light bulb mirrors and a lockable cabinet for personal belongings. Windows hover near the top of the high walls, letting in light (and the occasional field mouse), while rails packed with costumes are stationed all along the opposite wall.

I have been entrusted with six girls at one end of the room, while two other dressers take care of the rest of the room. Some of the chorus members have permanent positions, and over the years we have formed friendships. It’s so lovely to see them again, exchange hugs and grab a quick catch-up. Many other faces are new and unfamiliar though, and I will have to work fast at memorising who is who before they put their wigs on, which always completely transforms peoples’ appearance.

I plough through the costumes on the rails, furiously checking things off from my list and making sure the ‘pit pads’ are poppered into sleeves before the items get dragged to people’s desks.

The ladies, who will be playing a mob of devils, are looking amazing in maroon and moss-coloured velvet coats and doublets, stockings, and beautiful shoes that remind me of storybook illustrations from a vintage edition of The Shoemaker and the Elves. I meander from person to person, lacing up coats, coaxing stiff buttons, grappling with uncooperative shoe buckles. Outrageous, birds-nest-like wigs and ghoulish, grotesque masks complete the dark and unsettling look. There’s quite a bit of shrieking and laughter as the girls snap selfies with their phones.

Once everyone is dressed, I go upstairs to the side of stage, and find myself standing amongst a babbling milieu of devils and sprites as we all wait in the blue-tinged twilight of the wings.

‘So Pearl, you’re going to need to be over here to collect the masks.’ I am led across to the back of the set, and stationed with a basket by a towering structure of steps labelled ‘DAM OF FAUST TREAD UNIT A’. Blue fairy-lights are gaffa-taped to the framework, lighting the way.

The conductor, Robin Ticciati, readies himself for the launch of the rehearsal and I perch on the bottom step of the tread unit, listening as a hush begins to descend around us. Ticciati’s arms drift up from his sides as if of their own volition and a moment later, I hear the sound of Allan Clayton’s amazing voice climbing into the air.

Shortly afterwards, there is a thundering racket on the steps behind me. I jump up, grab the basket, and hold it out to collect masks as chorus members gallop past me. I wince as the delicate papier-mâché creations clatter in the basket, but on closer inspection, they have all survived intact. And with that, my assignment for the day is pretty much accomplished.

Orchestrating details

The schedule for today is listed as ‘Faust, stage and orchestra.’ It’s the first time I will have heard the orchestra - in this case, The London Philharmonic — since the last season, and the sound they make is nothing less than glorious, bringing the music alive with shivering, magical verve. Already the corridor outside the pit doors is cluttered with cello cases, and the sound of their locks clunking open echoes off the walls.

The schedule for today is listed as ‘Faust, stage and orchestra.’ It’s the first time I will have heard the orchestra — in this case, The London Philharmonic — since the last season, and the sound they make is nothing less than glorious, bringing the music alive with shivering, magical verve. Already the corridor outside the pit doors is cluttered with cello cases, and the sound of their locks clunking open echoes off the walls.

‘Pearl!’ calls Simon the timpanist as he wheels a giant kettle drum into the pit. He re-emerges a moment later to give me a hug and a kiss on the cheek. ‘How are you?’ He asks. As I reply that I’m doing well, he pumps my rib cage so that my voice comes out all vibrato, and what can you do but giggle? He’s been swimming that morning, he tells me, in an outdoor pool. ‘So invigorating,’ he explains.

‘Pearl!’ It’s lovely Lee, the tuba player.

‘How are the kids?’ I ask. ‘One’s a teenager and the other is warming up to it,’ he replies. Others are standing about amidst the rubble of instrument cases, making plans for the show. ‘It’s forty minutes until I play and then another forty minutes until I play again so I’m thinking, maybe I could go for a little run in-between? I feel I ought to do something.’

‘Well, I can’t run because of my knees…’ and so on.

Back in the ladies’ chorus dressing room, I’m lacing a singer into her dress coat. ‘I know I don’t really have to pee,’ she tells me, ‘It’s just a phantom feeling. It’s because I know that this will be my last chance for a very long time.’

The rehearsal gets underway. But as the morning progresses, the conductor keeps hauling everything to a stop and jumping back and forth in the score, which makes our plots, timed to the second, meaningless. Those of us who are not yet intimately familiar with the opera are quickly lost, and it doesn’t take long before I miss a cue for handing out masks. The chorus men are teasing me, loudly grumbling about how it’s such a lot of bother to have to bend over and pick their own masks out from my basket instead of having me hand them out. ‘Such a waste of time!’ says Andrew, winking at me. I sit back down on the bottom step of the tread unit, shrouded in the dark, and decide to stay put so that I don’t risk missing anything else.

As the musicians sweat it out in the pit and on the stage, the crowd of shadowy figures backstage are getting restless and bored, and have descended into burbling gossip and chatter.

'I do like a radish, but they’re very noisy.'

'I met the human sperm, and he was quite good looking actually.'

At lunch time, I am glad to escape the backstage darkness and dissolve into the magnificent, sun-soaked gardens. As wonderful as it can be, working backstage means a big sacrifice in daylight, so I sit by a warm wall in the rose garden and take off my socks and shoes, resolving to suck up as much vitamin D as I can. can’t be sure when our cues are coming up. On the way back in I pass Blossom, holding court in a corridor with a gaggle of makeup artists. ‘Does everyone know it’s the opening night party next Saturday?’ She’s asking.

‘Are you organising it, Blossom?’

‘No, I’m just interfering,’ she says, and starts counting off party tasks on her fingers. ‘So, we need to make sure the posters are going up, and that everyone knows, and that there will be transport, and fireworks on the lawn...’

During the afternoon, the chorus are being held captive on stage, which means their dressers can sneak into the auditorium to watch some of the rehearsal.

Exhausted singers and dancers are practically dragging themselves around the set, but the conductor will not let up on them. He makes everyone stop and redo a scene change, because someone carried off a table too noisily. I hadn’t noticed the distraction myself, but when they try it again, I can hear that the glimmering alchemy of the music is able to weave its spell unfettered. A few minutes later, he stops the orchestra again. ‘At the top of the crescendo, I want to hear a thpt - a poison dart.’ He stabs the air with his baton. ‘David, your vibrato was too fast.’ Piece by piece, as it comes together, the music combined with the libretto is stunning.

Chris Purves, playing Mephistopheles, steps downstage to deliver a monologue in French. Resplendent in ghoulish makeup and a wig that hangs past his ears like pond weeds, he looms over the orchestra as spooky lights play across his face. The unsettling drone of a deep, eerie bass tone colours the scene with an ominous ambience. ‘Shit, hang on,’ says Chris suddenly, fishing in his coat pocket as the drone plays on. He pulls out his lines, prompting himself.

Finally, we get around to the curtain calls, but the day isn’t over yet — it has been decreed that some earlier scenes need more work. Meanwhile, the wigs and makeup crews are necking caffeine in the kitchen to try and keep up.

When I finally make it back to Lewes, I have to dive into the supermarket and stock up on emergency energy fuel myself.

Golden Tickets

It’s only on my third illicit trip across the elegant courtyard to the Box Office, hot-footing it past the Long Bar and feeling conspicuous in my backstage blacks, that I find an envelope with my name on it has been left for me.

Today is the Final Rehearsal for Faust, and it will be performed in front of an audience of staff members. Company tickets, which are like gold dust, are rationed out at the beginning of the season and it’s a lottery as to which shows you will get tickets for. The private Facebook group for Company Members is jammed full of pleading posts, each piling in with increasingly grandiose offers of recompense in return for one (or several) of the coveted paper slips. Every time I agree to try and scrounge Company tickets for friends, I regret it. The politics of swapping or exchanging gifts for tickets can get stressful — and this, combined with the fact that most people don’t give up available tickets until the night before or even on the actual morning of the performance, means I have shut up shop on this one. However, I’ll do it for my parents, which is why I am waiting for someone I don’t know to leave tickets for me at the Box Office half an hour before curtain-up, and I have the heebie-jeebies. It’s only on my third illicit trip across the elegant courtyard to the Box Office, hot-footing it past the Long Bar and feeling conspicuous in my backstage blacks, that I find an envelope with my name on it has been left for me. Accustomed to dealing with the public, the Box Office staff are the epitome of efficient charm — all glamorous hair and warm, lipstick-drenched smiles — and I can heave an inward sigh of relief, safe in the knowledge that my parents will be able to see the show.

Back in the ladies’ chorus dressing room, all is bubbling along nicely. We’re now familiar with the costumes, and a routine is beginning to establish itself. I learn which girls are slower, which are messier, which like to get into costume early and which prefer to leave it until the last possible minute. I hate to badger people, invade their space or faff about unnecessarily, but I have to balance this against the goal of getting everyone up to stage on time, with all laces, buckles, neckties and buttons correctly fastened, and no forgotten watches sneaking out from beneath cuffs or personal jewellery glinting in the lights. I’m standing in the wings, my eyes razoring over the costumes for one final check when Suzi, another dresser, approaches me. Her charge, Ashley, has forty seconds to get out of one entire outfit and into another, and last time he didn’t make it back onto stage in time. ‘Could you help me?’ She asks.

In the half-light of one of the changing booths in the wings, Suzi tries to prep me. ‘We’ll have to take his boots off and then put them back on again,’ she says, ‘so he can change his trousers. Then he goes into this shirt — don’t forget the braces — then this coat. Check the fastenings. I’ll try and do his gaiters.’

‘OK,’ I nod. ‘Which side of the booth will he come in from?’

‘Could be either,’ says Suzi. And so, when the moment is approaching, we wait for his arrival, poised with sleeves rolled, like football goalies. Minutes later, Ashley comes flying in with makeup artist Annabelle in tow, and I am on the floor ripping open his boot-laces in the light of my head-torch. He’s not in his underwear for long, and about thirty-five seconds later, he is dressed again. ‘Wow,’ he’s saying, surprised relief in his eyes, ‘thanks so much! That was fast!’ And then he is gone again, and the three of us left behind in the booth are laughing from the adrenaline and high-fiving each other.

I take my place by the tread unit, and as the show progresses, snatches of conversation float past me.

‘I got to change a devil in a minute.’

‘It’s stuck to my eyebrow.’

‘Oh my God, my codpiece!’

‘Well, I hope you can get the blood out of that.’

‘When this energy drops off of me, I’m gonna be dead.’

‘My face was really itching and I was wondering if anyone would notice if I scratched it.’

And at the end of the show I hear, ‘They’re all really happy, well done everyone.’

Later that night, I’m standing in a field, the sky above me aflame with a beautiful sunset, when I receive a call from my parents. They’ve had a fantastic evening, full of magic and wonder and soul-journeying. Mum has fallen in love with Berlioz’s music, and Dad has been taken back to a time in his life when he was teaching at RADA, and his days were jam-packed with energy, creativity and excitement. He tells me that he took it upon himself to personally thank the director for all of his hard work in creating such a brilliant show. At the end of the conversation, I hang up with a happy sigh. THIS is what art is for.

Princesses and wood-wagglers

During the morning, we are in the auditorium, watching some of the chorus girls rehearsing the water nymph scene. They are suspended high in the air on wires, and they are swirling thirty-foot long mermaid tails that brush the stage floor far below them. The effect is really quite breathtaking — they absolutely look as though they are under water.

‘She’s Russian,’ says wardrobe assistant Leah, conspiratorially. Raindrops spill down the windows of the Running Wardrobe headquarters as she passes me a photograph of an elegant woman. ‘But she’s friendly.’

‘I see,’ I say, studying the face. I turn and run my hand along a length of silver satin that hangs from the door beside me, fashioned into a beautiful, figure-hugging dress. ‘And how much time do we have?’

‘Six minutes. Do you think you can do it?’

I nod thoughtfully. ‘Leave it to me.’

That’s six minutes to strip ‘The Foreign Princess’ out of a cream coloured two-piece suit and whip her into this silvery concoction, plus jam on some jewellery. Acres of time. Plus, we’ll be in the cage at the side of the stage, meaning that once the ‘Princess’ is ready, she will be able to leap to the stage in half a heartbeat. I know the dress rehearsal will be fumbly, but overall, I am feeling confident. We’ll need to work out the change choreography so that wigs and makeup can also do their bit, and then we’ll hit a groove. It’ll be fine.

Today is Dresser Training Day for Rusalka, Dvořák’s operatic interpretation of The Little Mermaid that will be sung in Czech. I have been charged with five principal singers, meaning I will be on the Circle Level corridors, where the principals reside.

This is the third time this production has been revived at Glyndebourne, and it’s a firm favourite among my colleagues. The music is beautiful. The design, by Rae Smith, is charming and brings to mind a timeless rustic fairytale. The direction is by Melly Smith - I once met her sister on a train but that’s another story.

I went to see this show when it was performed in 2012. I remember the scene in the woods, where the Prince is hunting a deer. The deer was moving about the stage with the theatrically clever yet simple gesture of holding two small antlers to her head. I don’t remember the details of the story, but I do remember the rolling feeling of sweet sadness as the final notes died against a visual of fading, twinkling lights, and that I had to root around in my bag for tissues to catch the tears that were slipping down my cheeks. On the website, Glyndebourne introduces the show with the question, `what would you sacrifice for love?’

During the morning, we are in the auditorium, watching some of the chorus girls rehearsing the water nymph scene. They are suspended high in the air on wires, and they are swirling thirty-foot long mermaid tails that brush the stage floor far below them. The effect is really quite breathtaking — they absolutely look as though they are under water - but I always smile when I remember the story of one girl who somehow got lowered down facing the wrong way, with her back towards the audience. During the scene, she was slowly rotated around until she was facing the right way, but this somehow just made the whole incident even funnier.

The most famous Glyndebourne Rasulka story of all, however, is the one about the time the leading lady, wrapped in her mermaid tail, rolled off the edge of the stage and landed in the orchestra pit, smashing my friend Santiago’s cello. ‘I was in all the papers,’ Santiago told me. ‘I wanted to be famous for being a good cellist, but I’ll take whatever I can.’ He showed me the cello in question — a honey-coloured thing of exquisite beauty, especially made for some exotic prince in the 1620s, and worth apparently as much as a house. There was a stamp inside to certify its story. Glyndebourne paid for the instrument’s repair, and, so says Santi, it now sounds even better than before, since the restorers discovered a hidden crack that they think had been there for about 100 years.

But back to today. I watch as Ms. Smith strides among her cast on the stage, adjusting a movement here, refining and defining a reaction there. Her short silver bob flips about her face as she spins and turns, holding all the singers and dancers who are gathered on the set in her energetic force-field. When the scene is re-wound and played again, the modifications, deceptively subtle, make a clear impact. The storytelling is instantly and undeniably clearer and more powerful.

Later, in the green room, I am chuckling with the other dressers as a tannoy announcement comes through the speakers. ‘Stand by, Flying Nymph Operators’ - a job description that surely anyone would love to have in their passport. But then there’s an even better one: ‘Stand by, Wood Wagglers.’ Quite who these mysterious Wood Wagglers are and what they do is still a mystery, but perhaps all will become clear during next Monday’s full dress rehearsal…

Puppets and head explosions

The atmosphere is shimmering with a low level buzz of anticipation. Performers begin to emerge, transformed, from their dressing rooms and everyone is looking as though they have just stepped right out of a fabulous Edwardian children’s book illustration. The costumes are amazing - stunning fantasy has been woven through the historical references with smile-sparking wit and imagination. Tailors and seamstresses are clustered in the corridors, tape measures draped around their necks, frowning with concentration as they scrutinise their handiwork.

It’s the first day of dress rehearsals for The Magic Flute, and the dressers’ team are gathered in the Running Wardrobe head-quarters painfully early. For some of us, it feels like it’s only been a few hours since we were putting away last night’s show, but that’s how it goes at this time of the season, when the pace is gunning at full-steam.

I am handed a slim stack of stapled notes with my name pencilled on the front. This is my show plot, which details the movements and costume changes throughout the performance of my assigned artists, and is timed to the second. Changes usually happen either in the dressing rooms or in the side-of-stage quick-change booths. ‘Out of black trousers and patent shoes, into blue trousers and lace-up boots. VV quick!!’ On separate sheets we have meticulously comprehensive lists of all costume items, right down to socks, bras, show pants, watches, earrings, and pocket handkerchiefs. It will our job at the beginning of each evening to comb through the items on the dressing room rails and the bit bags, which contain all the odds and sods, and it will be our responsibility to hunt down anything that might be missing. Usually, missing things will have turned up in someone else’s dressing room, or if they got lost on stage, there’s a chance that Stage Management will have them. Often, singers accidentally go home in their show socks and forget to return them. Replacements will be procured, but not without a disapproving frown.

I collect a plastic basket filled with freshly folded towels, and I head to the under-stage dressing rooms to meet my charges for this show — four puppeteers who turn out to be bright and beaming young men. I’ve heard rumours that they have worked with Cirque du Soleil and on Warhorse, but there’s not much time for chitchat today — I’ll ask them another time. Often, I find that singers can rely on dressers to shepherd them through the costume plot, but these guys are sharp as pins, and they pore over my notes with me to get clear in their heads about when and where they are meant to be wearing what.

The atmosphere backstage is shimmering with a low level buzz of anticipation. Performers begin to emerge, transformed, from their dressing rooms and everyone is looking as though they have just stepped right out of a fabulous Edwardian children’s book illustration. The costumes are amazing. Stunning elements of fantasy have been woven through the historical references with smile-sparking wit and imagination. Tailors and seamstresses are clustered in the corridors, tape measures draped around their necks, frowning with concentration as they scrutinise their exquisite handiwork.

‘Holy moly,’ says wig-technician Dee as she examines the men’s chorus chef hats — giant creations with internal wiring and a battery pack so that they can be illuminated via remote control. ‘I think this one’s going to be a corker!’

There are some errors on my plot, instructing me to set incorrect items of costume in the Opposite-Prompt quick-change cage, and also some hats are missing. But wardrobe-assistant Leah barks questions into her headset, and we soon get everything all straightened out. My agenda is to keep everything in my little corner of control as calm and as zen as possible, and so far this plan seems to be working.

After Act 1 has been rehearsed, all dressers are called to the Running Wardrobe headquarters for notes with the costume supervisor, Caroline, who is part of the designer/director Barbe & Doucet’s team. This has never happened before — the exacting standards that Barbe & Doucet have set are unprecedented. With her salmon pink cardigan, necklace of rose quartz beads and softly spoken voice, Caroline has the demeanour of a gentle primary school teacher and yet the severity of her silver bob and the unbending line of her eyebrow suggests that not even the tiniest detail could hope to slip past her attention. She runs through each member of the cast, addressing the appropriate dresser in turn, and drills through the list of notes she has written into a hard-backed notebook with an expensive looking fountain pen. The men’s chorus dressers get a detailed demonstration on how to fit the neck-ties correctly — the knots must be just so. Fortunately, I already answers ready for her queries about the missing puppeteer hats and ill-fitting belts.

At lunch time, I’m happy to wander into the furthest reaches of the gardens and disappear amid a cacophony of cricket song. I lie back on the warm, glossy grass and allow the sunshine to melt across my eyelids, gently sponging away any stress from the morning.

In the afternoon, i find the Circle Level kitchen is stinking of instant coffee, and both the kettles are rattling furiously as everybody gears up for Act 2. The men’s chorus materialise from their dressing room and congregate in the corridor while waiting for their hats to be fitted. I notice that Mike is wearing knee pads underneath his gigantic, teepee-shaped pastry chef’s costume. Then I remember that he’s drawn the short straw yet again — he will be playing a dwarf, and will be performing on his knees. He gives me a sardonic eye roll and gestures at the costume. ‘Inspiration for one of your paintings perhaps, Pearl?’

I head up to the Promt-side wings in preparation for a quick change, and discover a fifteen-foot high suitcase is being wheeled onto the stage. The crew are clearly struggling with the weight of it, and they almost squish stage manager Claire into her Prompt Corner desk, but nothing, it seems, can distract her from calmly continuing with her announcements into her little microphone; ‘Electrics, this is your call for the pyro head explosion, thank you.’

Two of the puppeteers are getting strapped into harnesses which are attached to gigantic, robot puppets that look about as tall as houses. Their massive heads are wobbling around somewhere near the rigging. I pull the puppeteers’ jackets on over the harnesses, before crouching down to help them into boots that are attached via rods to the puppets’ feet. Each puppet is flanked by three other operators — one for each of the arms and one for the head, using long poles. I step back as the huge figures turn around, and begin to carefully manoeuvre towards the stage, dwarfing everyone around them.

In about ten minutes’ time, when they come back off stage, I will have thirty seconds to get one of the puppeteers out of his jacket, harness, and puppet boots, and then into a black cloak, black gloves and black shoes. Standing in the darkness of the wings, I roll each glove down, ready to shove onto his hands, and tuck them inside-out into my pockets. Then I drape the cloak over my shoulders so that I can easily whip it off and wrap it around him. I stand ready and waiting while my colleagues hover nearby, poised to catch the other puppeteers like shadowy football goalies. It’s going to be intense, and big scene changes will be going on around us at the same time, so we’ll need to have our wits about us to keep from getting mown down.

Sure enough, a few moments later, the puppets lumber off the stage and stride back into the wings just as huge pieces of scenery start to rumble by. ‘Mind your backs! Stand back! Stand back!’

I find myself clambering in between giant puppet legs to help Jack out of his boots and harness. As the puppet is wheeled away, I rip the gloves from my pockets, jam them onto his hands, and then pull the cloak off my back so that he can dive straight into the sleeves. I’m thankful that Rachael has dropped down to the floor to help him with his shoes while I scoot around behind to snap together the cloak’s magnetic fastenings down Jack’s back.

‘These are gonna need elastics!’ Rachael yells over her shoulder as she struggles with the shoelaces, and Leah duly scribbles notes. Done — we are done! And the puppeteers, now magically invisible in their cloaks, glide back to the stage.

The day eases to a close and as we are rehanging and sorting costumes, Dee calls to me, ‘You always look so calm, Pearl!’

‘Ah,’ I reply, ‘it’s all just an act!’

Hi-ho, hi-ho

‘Oh man,’ says Sahel as the staff bus rumbles out of Lewes, shaking his head with a smile, ‘you know it’s bad when you need a fourth cup of coffee by the afternoon!’

‘Fourth?’ says the older man sitting next to him. ‘More like tenth.’

Sahel’s infectious laughter is bubbling up again, and I think to myself that if someone as rubber-ball bouncy and bright as Sahel has been finding the schedule punishing, then I am fully entitled to my own mind-deadening tiredness.

‘Oh man,’ says Sahel as the staff bus rumbles out of Lewes, shaking his head with a smile, ‘you know it’s bad when you need a fourth cup of coffee by the afternoon!’

‘Fourth?’ says the older man sitting next to him. ‘More like tenth.’

Sahel’s infectious laughter is bubbling up again, and I think to myself that if someone as rubber-ball bouncy and bright as Sahel has been finding the schedule punishing, then I am fully entitled to my own mind-deadening tiredness.

‘We’re all very tired,’ Boss Lucy is saying as we pile into Running Wardrobe. Her face looks as though it’s literally melting with exhaustion. ‘We’re going to have to pull together tonight — I’m going to need your help to get this show turned around. Flute has just been… insane. The stage crew are shattered, props are on their knees.’ We’re all nodding. ‘I know everything will be fine, and once the show is up, it will be great — we just need to get through these next few days.’

‘How are you doing?’ I ask the chorus ladies as I dish out hats and tights in their room.

‘Oh, hanging in there!’ They shrug and laugh at the craziness of it all.

‘Have you seen next week’s schedule?’ Jade cries, holding up her phone. ‘No more rehearsals! Just shows in the afternoons!’ and the girls let out a whooping cheer.

‘Just one more day to get through,’ says Natalia, and it’s the same for me. The dressers and makeup girls are swapping notes about how nobody’s done any vacuuming for weeks. But it’s just one more ‘double-decker’ day of rehearsals in the morning and a performance in the evening, and then for the rest of the season I’ll just be working on shows and I’ll have my mornings back again.

Blossom has brought in some dinner for me that she has cooked at home — a plate of roast lamb and baked sweet potato. She has noticed that I have been a little run down, and the kindness of her gesture almost brings tears to my eyes. I sit and eat it in the green room, watching people exchange smiles as a member of the orchestra snores thunderously on one of the couches. The dinner is delicious.

At the end of the show, we all pitch in upstairs like Snow White’s dwarfs to help Boss Lucy and the team with the Cendrillon laundry. Washing machines are growling and rumbling, the hand-wash spinner is whirring. Coat-hangers are clanging and the hot-box door is slamming open and shut. Already, the ladies’ chorus black mesh tops are drip-drying on a rail, and the girls only took them off about twenty minutes ago.

‘Alright, thank you everyone,’ says Claire, her face flushed with steam, ‘I think that’s all we need you for.’

Alison gives Blossom and I a lift back into town. Blossom is trying to entice us to join her for cocktails at the new rooftop bar above Chaula’s that her son is managing, but Alison and I are way too wrung out, and we promise to do it another time. As I spill out of Alison’s car, I give her peck on the cheek and say, ‘see you in a few hours!’ Back at home, there’s just enough time to shower, lay out tomorrow’s clothes and have a hot drink before it’s time to turn in…

Sweating it out

The stage crew are still setting the stage, and red DO NOT ENTER tapes are pulled across the entry door, meaning we cannot pre-set our quick-changes backstage. Apparently Rinaldo had been rehearsing on stage this morning, and the crew are struggling to switch everything over to the mammoth Magic Flute on time. When they first tried this change-over, it took them seven hours. So far today, they’ve been at it for four, which is a bit ominous.

‘No notes today,’ says Boss Lucy, struggling to raise her voice above the fan that whirrs furiously on her desk. ‘I haven’t had any messages to say that anyone’s off. But it’s very hot, so take it easy. Don’t push yourselves, drink plenty of water and let me know if you’re not feeling well. Have a great show!’

The stage crew are still setting the stage, and red DO NOT ENTER tapes are pulled across the entry door, meaning we cannot pre-set our quick-changes backstage. Apparently Rinaldo had been rehearsing on stage this morning, and the crew are struggling to switch everything over to the mammoth Magic Flute on time. When they first tried this change-over, it took them seven hours. So far today, they’ve been at it for four, which is a bit ominous. If the show runs late, rumour has it that Glyndebourne will pay Southern Rail something in the region of £100,000 a minute to hold the London train at Lewes station until the patrons are on board. So, the pressure is on — but in the end, the curtain is only fifteen minutes late going up. I have to rush around and set my changes once the show has already started, and even then, the crew are still flinging things into place with slightly mad looking eyes.

I squirrel myself away in the Opposite-Promt quick-change booth, waiting for the puppeteers’ first change. My face is aglow in the light from my Kindle as I suck up Stephen King’s The Green Mile, while The Magic Flute thunders along on the other side of the black felt curtain.

After the interval, I hover in the wings so that I can listen to the Queen of the Night’s famous aria. Standing in a glittering purple dress, Caroline Wettergreen is belting out some shockingly high notes, and I imagine champagne glasses exploding all over the lawns. I’ve heard from her dresser how nervous she has been, but there’s no sign of any cracks on stage tonight. As she sweeps off the stage for a grand exit, three pyrotechnic detonations blaze flashes of light into the wings. I had forgotten that they happen, and I am laughing with shock, my hands plastered over my face.

The next day, the temperature outside climbs perilously high, and the hillsides are turning brown in the baking heat. On Cendrillon, the air backstage feels heavy, like it’s literally permeated with sweat. While I’m doing the ladies’ chorus quick change, their bodies are slimy and wet. The costumes are sopping, and I feel I could almost wring them out. When I pull my head torch up onto my forehead, it slips back down my shiny face, bumping my nose on the way. There’s no time to reposition it but luckily Claire steps in and shines the beam of her own torch onto the fastenings of my costumes for me.

When I go upstairs to the green room for the dinner break, the heat makes it feel as though we’re in another country, like Jakarta. Bodies are draped over the sofas and armchairs, and no one’s got the energy for conversation. I find a chair near Alison, and we sit by an open window that has no breeze coming through it. I’m mindlessly scrolling through Instagram on my phone when I become aware of a presence crouching beside me — it’s Boss Lucy. She tells me that Gemma has had to go home, and wants to know if I can cover her plot, which is with the male dancers. So I hurry back down to my post outside the ladies’ chorus with the show’s master plot, and start to wade through the pages to see what the male dancers will be getting up to. But soon Claire appears and says the plan has been changed — Angela will be looking after the dancers and I am to take care of the Step Mother’s quick-change. My heart is doing a quick-change as I gallop up to the Principals on the Circle Level and find Agnes, who plays Cinderella’s step-mother. I knock on her door and sidle into the room.

‘Hellooo,’ says Agnes in an accent I can’t place. She’s standing with her legs astride in an A-formation with her hands planted on her hips, like some kind of extraordinary superhero. She’s wearing an enormous pair of pants with suspenders, and a bra that looks like it might have been pinched from Madonna.

‘Hi,’ I say, ‘I’m going to be doing your quick-change today.’

‘Ah, okaay,’ says Agnes. ‘Is fine, we have the time.’ And she waves her hands, batting away any concerns. ‘I show you.’ Her bright blue eyeshadow sparkles as she gives me a poker-faced wink, and I give her a nod and a double thumbs-up.

After the second half has launched, I check my watch multiple times for fear of missing the change, but I show up at the quick-change booth in plenty of time. Soon enough, Agnes comes striding in. She’s already in her underwear as she kicks off a pair of glittery gold shoes and then points to a corset. ‘This first.’ And then I’m grappling with unfamiliar fastenings that twist in ways I don’t expect. It’ll be fine, it always is, I tell myself, and it is. Next the skirt. Then she sits in a chair in front of the mirror for her wig and makeup changes, while I fasten on a gaudy necklace, and hand her her rings and bracelets. She slips her own feet into a new pair of shoes. And we’re done. I give her another thumbs-up in the mirror, and she gives me a grin of thanks.

Back downstairs at the end of the show, I strip the chorus girls out of their costumes. They apologise for being so sweaty but I implore them not to worry, it’s all part of the job. Years of ripping out pit-pads and handling sweat-soaked costumes have rendered me completely un-squeamish but even so, at the end of the night, I am standing over the kitchen sink on the Circle Level, soaping my arms up to my elbows. Ahhh! Living the dream.

The show must go on

The lights overhead flicker, pop, and then cut out. Suddenly, everything is plunged into the semi-darkness of emergency lighting. The intercom is dead, and the opera has ground to halt. The monitor screen is black. I hear a thunderous rumbling coming from the stage as the safety iron hurtles down, and then the fire alarms begin to wail. I turn to catch eyes with my colleagues, and no one is smiling. This is not a drill.

Flute Performance Number 9 is unfolding nicely, albeit with an understudy replacing an indisposed Queen of The Night. I’m sitting in my usual spot by the refrigerator in the under-stage corridor, outside the men’s chorus and the Puppeteers’ dressing rooms. An assortment of wigs technicians and makeup artists sprawl in adjacent chairs alongside me, scrolling on their phones while they wait for cues and changes. I’m watching a monitor fixed to the wall, that shows what’s happening on the stage. Occasionally, someone will try to sneak the channel over to football or Love Island. Dresser Adeline fishes a whistle pop out from her bag, and reduces us all to tears of laughter as she tries to work out Beethoven’s 5th on it. We’re suggesting that she ask the conductor if he’ll let her join the orchestra when it begins to melt in her mouth, so she crunches it up and retires to a table in the costume store to do some drawing in her sketchbook.

I check my timer. It’s forty minutes into the show, and coming up for one of the puppeteers’ side-of-stage quick-changes. I stand up, and am just checking that I have my head-torch with me, when the lights overhead flicker, pop, and then cut out. Suddenly, everything is plunged into the semi-darkness of emergency lighting. The intercom is dead, and the opera has ground to halt. The monitor screen is black. I hear a thunderous rumbling coming from the stage as the safety iron hurtles down, and then the fire alarms begin to wail. I turn to catch eyes with my colleagues, and no one is smiling. This is not a drill.

Right, I think. Just follow the motions. I go back to my chair and as I reach for my bag that’s tucked beneath it, I am trying to remember where the emergency meeting point for dressers is in the gardens — it gets changed every year. Chorus singers and a couple of the puppeteers spill out from their dressing rooms — ‘what do we do? Do we leave the building? What’s happening?’

By now, the fire alarm is stopping and starting, meaning we are all caught up in a frozen limbo of confusion. ‘Wait,’ says wardrobe assistant Leah, ‘let’s just hold on for a sec.’

We can hear footsteps running down the corridor, and Tristan from stage management screeches around the corner. ‘Stay here,’ he instructs, ‘just stay in your dressing rooms.’ In lieu of a working intercom, he is literally having to physically sprint around the building in person. ‘Don’t go anywhere,’ he says, ‘I need to know where you all are and where I can find you.’

‘What’s happening?’ Leah asks him.

‘I don’t know,’ he says with a panicked shrug, and then he shoots off again.

I sit back down, and notice that my knees are shaking.

‘Oi,’ Leah calls after a couple of chorus men who are beginning to make their way down the corridor. ‘Where are you going?’

‘To make a cup of tea.’ They hold up their mugs.

‘And how are you going to manage that without a working kettle?’

They look at each other. ‘Oh yeah…’

It occurs to us that the power-cut might be wider spread than just Glyndebourne, and I reach for my phone to see if Twitter might be able to offer any answers, but just as I discover that there’s no internet, I hear an anguished cry from inside the men’s chorus dressing room — ‘No internet? What are we going to doooo?!’

Adeline quietly continues with her drawing in the costume store, working by the light of her head-torch.

Boss Lucy appears. She’s making her way around the building to check on all the dressers, and she hands Leah a battery powered walkie-talkie so that all of the Running Wardrobe assistants can keep in contact with each other.

Nobody’s quite sure why the Glyndebourne generator hasn’t kicked in, but a few performers who have trickled back from the stage have some snippets of information for us. All the bigwigs of the company have gathered at the side of the stage in the Prompt-side wing, which is apparently is the protocol for situations such as this. And the upshot? Nobody knows what has happened, and nobody knows what to do. This news sets everyone off into gales of adrenaline-spiked laughter. Then we hear that the auditorium is in pitch blackness and the worker lights are not working, which means the audience have had to stay put. We wonder what they are all thinking, sitting there in the darkness. As the minutes tick by, the next piece of news filters through — the management are trying to decide if the show should be abandoned and the audience reimbursed, or if they should wait and hope for a return of power and pay everyone overtime, and in which case, how long they should wait for.

The lights come back on. Then they go out again. And then they come back on again once more.

Leah’s walkie-talkie crackles — ‘Lights are on in the pit.’ We hear that the building management department are turning the power back on in different parts of building one section at a time, to ward off the risk of a power overload. Next to come back are the auditorium lights, and the audience are finally released into the gardens.

Stage management Claire’s voice comes over the intercom — ‘This is a test call.’ She then informs the company that we will restart the show, picking up from where we left off, but that it will take about half an hour to get everything back on track.

‘Alright then!’ says Leah, throwing up her hands with an overwhelmed laugh. ‘I guess that means go take a tea break!’

I make my way to the Courtyard canteen, and find it packed with orchestra. They’ve probably been in here the whole time. By now the internet is back on, and we learn that the power-cut was not just us, but has affected a large part of the country.

Calls are going out for principal singer Bjorn, who has gone awol, but once he has been rounded up and returned to his dressing room, we are ready to restart the show. I pass the Front of House manager Jules as I make way back to the under-stage corridor. She’s speaking into a walkie-talkie — ‘…if you could start to encourage them back in…’

I head back to my spot by the men’s chorus, and see that the monitor has come back to life. Jules is making her way across the stage in front of the safety iron, illuminated in a pool of light. She stops to make an announcement, and Leah stabs at the volume button on the remote control so that we can hear what she is saying. She’s thanking the audience for their patience, and informing them that we will be finishing an hour later than scheduled, but that the Glyndebourne transport will get them back to Lewes in time to catch later trains to London, and that Box Office staff can help with ordering taxis.

Then the safety iron rattles up again, revealing that the stage behind it is all lit and ready to go. The conductor returns to the pit, and Sofia Fomina reappears on the stage as Pamina. She curtseys cutely for the audience, who roar with applause and cheers, before she reenacts the faint she had performed just before the power had cut out. The music swells up again, and we are off once more, almost an hour behind schedule.

The show will indeed, go on.

Curtain call

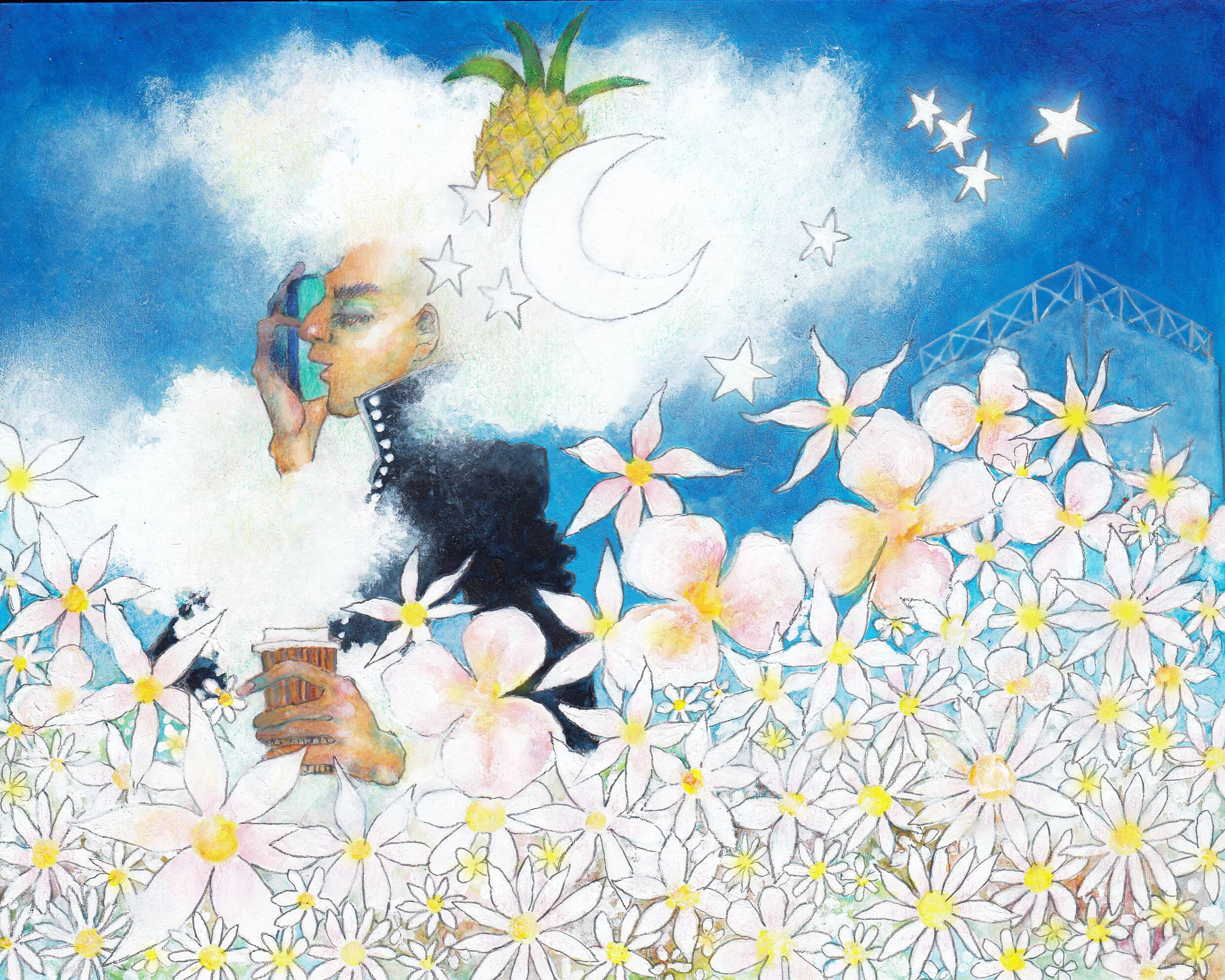

I wander back out into the gardens, and take a moment to stand beneath the glittering, gleaming, silver crescent moon.

So there it is. Another summer at Glyndebourne... gone with a glimmer and a wink.

Dresser Alison is not at her spot in the Foyer Level corridor, which means she must be backstage somewhere. So I skip down the stairs and slip in through the door to the stage, where I am instantly engulfed in blue-hued darkness, and the impassioned lunacy of Mozart’s Magic Flute. Figures loiter in the shadows, either waiting to go on stage, move scenery, or work on a change. I make my way towards the back end of the Prompt Side wings, weave my way past giant pieces of set, and twist around a corner into a hidden quick-change booth. And there is Alison, looking up with a surprised smile to see me. I lean down and stage-whisper into her ear — ‘I need to ask you something a bit cheeky.’

‘Oh right?’

‘Can I have one of the biscuits that are in your locker?’

She laughs. ‘Of course, darling! Please, help yourself.’

My clean-eating diet goals have gone out the window during these last two weeks of the season. I need caffeine and sugar to propel me through the unrelenting schedule, and tonight will be — surreally — the final Flute and also my last night of the season. The previous evening had been the final Rusalka, and at the end of the show, I’d gone to the side-of-stage to watch the curtain calls. I had looked up with enraptured glee as the water nymphs were winched high into the air, and then pulled across the stage, hidden behind black drapes, before dropping down in front of the audience. The applause had been thunderous, with all the back-stage monitors trembling as the audience hammered the auditorium floor with their feet, whooping and whistling.

At the long interval, the dressers gather in the Running Wardrobe mothership. Claire has ordered in pizza — it is without doubt the worst pizza I’ve ever had, but as we chew and chatter, the mood is warm and bubbly.

Before long, the other, stage-management Claire, calls the half-hour, and we head back to our posts.

Once the show has come down and the laundry has gone up, I am back in the kitchen again, moving out of my locker with an ache in my heart. I load into a large shopping bag my flask, my head torch and my spare batteries, my knee pads, my spare lanyard, my show notes, my black apron, my emergency deodorant, and mints. I also take out a bottle of prosecco and a chocolate tart, which I carry with me into the gardens. The evening outside is utterly magical, nestled under a star-drenched sky. I find that Alison has procured a table in the perfect spot, at the top end of the lake, and I join the group of dressers that are gathered around it. We load up the table with our goodies and, in the light of Alison’s solar-powered moon lantern, we sit back in the soft warm breeze of the night, and our conversation mingles with with the clink of glasses, chatter and laughter of the punters gathered in nearby corners.

‘Let’s come back for the final-night-party tomorrow,’ urges Blossom, and plans are quickly hatched. The final show of the season will be Rinaldo, which I’m not working on. The break-dancing counter-tenor Jakub Józef Orliński, who has been a huge hit on Instagram, will be heading up the cast.

So the following evening, like a bunch of well-dressed, over-age teenagers, Alison, Suzi and I meet in the car park behind the Premier Inn. We exchange compliments on each others’ outfits, and then Suzi drives us all to Glyndebourne. It turns out that we’ve arrived way earlier than we needed to, and the third act is only just launching. So we settle into the green room, and Alison gets the night underway with a bottle of wine and we watch the show on the green room’s large TV screen. The audience ooohs and ahhhs as Jakub manages to sneak in some flashy dance moves. The pyro-technics literally go off with a bang, and it’s clear that the energy is high, both on stage and in the auditorium. Once again, as the curtain comes down, the audience are going wild.

Every year at the end of the season, Glyndebourne’s Executive Chairman Gus Christie will come on stage to give a speech, and I am curious to hear it. So I sneak through the secret door at the back of the kitchen that lets you into the auditorium, and prowl along the back wall behind the rows of well-coiffed heads, hidden in the shadows. I reach a point where I can just about see Gus if I stand on tip-toe. He is talking about how none of this could happen without ‘you, our wonderful audience. So thank you.’ He goes on to say how the House has reached 92% of its targets this year, which is admirable given that Glyndebourne receives no public funding. But, in these uncertain times and with changes ahead, this will become more of a challenge. Glyndebourne will continue to employ singers, conductors and directors from Europe, and will continue to work with European suppliers and partners, even if this means that costs will rise.

This news is greeted with applause.

Gus makes a whistle-stop tour of all the fantastic productions that we have staged this year, and introduces the programme for the following summer. Whoops and cheers go out as he names singers, conductors and directors, including Barrie Kosky of Saul glory, who will be making an appearance. Then he goes on to talk about the Jerwood Young Artists programme that supports exceptional new singers with coaching and performance opportunities, and apparently Sahel Salam and Noluvuyiso Vuvu Mpofu have both been recipients this year. When Gus admits that The Royal Opera House beat Glyndebourne at a cricket match earlier that day, the audience cheerfully boos.

By this point, I feel that I’ve heard enough, and I sneak out again. I find that the show has been put to bed and, clutching paper cups containing a few fingers of Champagne, the dressers are gathering on the Upper Circle terrace to watch as fireworks explode in the sky like huge, mushrooming fire flowers.

The final-night party is already underway in the Mildmay restaurant, and the PA is booming with music from a live band who are playing covers of rock tunes. It doesn’t take long before the dance floor is rammed, but I’ve been keeping an eye on the time. The hour of midnight is fast approaching, when the final Cinderella pumpkin coach will be leaving for Lewes.

‘You’re not leaving?’ A drunken, beautiful girl I don’t know is batting her bejewelled lashes at me as I gather up my bag.

‘The last bus is leaving,’ I sigh.

‘When?’

‘Midnight.’

‘What time is it?’ I nod at the giant clock right behind her head, with its hands inching their way towards the perpendicular hour.

‘Oh staaayyyy,’ pleads the girl, hanging onto my arm. ‘We’ll get an Uber.’ I break out into a smile. ‘Okay.’

I wander back out into the gardens, and take a moment to stand beneath the glittering, gleaming, silver crescent moon.

So there it is. Another summer at Glyndebourne... gone with a glimmer and a wink.